A History of Pressing Flowers for Art

Botanical preservationists have looked to drying flowers for a multitude of reasons; from the scientific to the sentimental. We often think of botanical preservation as a scientific means to document the native flora and fauna of a place. However, it existed as a form of art before it became a part of the scientific world. Though it can require skill and patience, flower pressing does not require specialised equipment, which makes it an appealing art form. Often it is a therapeutic pastime, with satisfying end results.

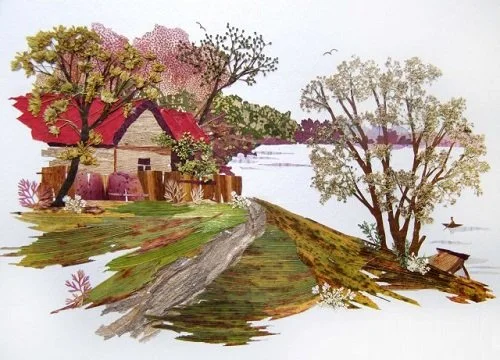

Specifically as an art form, flower pressing originated in Japan and is known as ‘Oshibana’. The term refers to using dried flowers to create a whole picture, such as botanicals placed together to create an image of a landscape. 16th Century Samurai would also practice Oshibana to promote patience, concentration and a connection to nature.

As trade increased with Japan in the 1800’s, so did the Western fascination with Oshibana. It became a favourite pastime, especially amongst women in the Victorian West. Flowers were believed to have hidden depths and meanings, and were often used as an alternative language to express themselves in an otherwise strict and conservative Victorian society. As a result, pressing them became a treasured hobby, preserving sentimental meanings and memories. Notably, Gertrude Tredwell created a collection of scrapbooks of pressed botanicals from her travels in the White Mountains during 1865, which can still be viewed at her family home in New York.

Pressed Flowers and seaweed from Gertrude Tredwell’s collection, which are held at Marchant’s House

As well as a hobby, the arrangement of flowers specifically for display and therefore as a form of art also became more popular in the 1800’s. Interestingly, the Western Reserve Historical Society has in its collection a preserved bouquet from the grave of Abraham Lincoln, which was pressed and displayed in 1865. A lasting gift for a former President. It was also during this time that books cataloguing flowers from sacred sites such as Bethlehem, Jerusalem and Mount Carmel became popular souvenirs and mementos from sanctified places. The flowers and leaves would be arranged in specific shapes to create images, such as a cross or a vase, and each page is labelled with the name of the site. The books would have an olive wood front and back to preserve the arrangements. A number of museums now hold copies, including the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. The combination of using something physical from a sacred place, with picturesque artwork was appealing as a souvenir, and the preservation of colours is often fascinating to see.

‘Flowers from Bethlehem’, from a copy held by the MAAS

Unfortunately, Oshibana has often been considered a mere hobby or pastime, rather than a recognised and established art form, though some individuals have (and are) trying to change that. The 1980’s saw a resurgence of using pressed flowers for art and in 1983 The Pressed Flower Guild was established to celebrate the talent and skill of pressed flower artists from all over the world. It was also during this time that actress and Princess of Monaco, Grace Kelly helped promote Oshibana in her book ‘My book of Flowers’.

What’s most interesting about the history of botanical preservation for the purpose of art is that it extends back even before 16th Century Japan. Archaeologists have unearthed dried botanicals in graves dating back 3000 years. Floral collars using cornflowers, poppies and olive leaves, and pressed laurels and garlands have been discovered in Egyptian graves, demonstrating the importance of flowers and botanicals in adorning both people and places. In 2016, The Guardian reported a 3000 year old preserved thistle had been unearthed in Lancashire as part of a Bronze Age archaeological dig. What this shows is that flowers have held deep and significant meanings for us for centuries; their shapes, smell and colour have been used in decoration for thousands of years and connects us with the natural world, something we continue to value today. With an ever-increasing focus on issues such as climate change and ongoing destruction of the natural world, people’s attention often returns to nature and its preservation. Many modern societies and individuals uphold the value of the natural and organic; in a fast-paced world, people are choosing clean (and ‘slow’) living, bringing nature into the home and valuing it as part of their lifestyle and decor too. Flower pressing has seen a resurgence in recent years, possibly as a means to reconnect with nature, slow down a little and appreciate what is around us.

Whether for art, botanical study or sentimentality, flower pressing is certainly a rewarding and therapeutic pastime. Pressing leaves and flowers alone can often require skill and patience, but creating art from the end results is a centuries-old creative process, and will hopefully continue to become a more recognised, established form of art.

Ann Haddad, ‘Nature for Ladies: The Victorian Art of Flower and Seaweed Pressing’, 2017 https://merchantshouse.org/blog/seaweed-pressing/

Sbrosious, ‘Pressed Flowers’, Western Reserve Historical Society, 2020 https://www.wrhs.org/blog/pressed-flowers-history-and-tutorial/

The Pressed Flower Guild, https://www.pressedflowerguild.org.uk

Gwen Robyns, ‘My Book Of Flowers’, 1980, Doubleday Publishing

Dalya Alberge, ‘Pristine pressed flower among ‘jaw-dropping’ Bronze Age find, 2016, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/sep/30/pristine-pressed-flower-among-jaw-dropping-bronze-age-finds

Margaret Simpson and Judith Campbell, ‘WW1 Souvenir ‘Flowers of the Holy Land Jerusalem’ book’, 2017, The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences https://collection.maas.museum/object/559522

Tatiana Berdnik, Oshibana, 2012, https://viola.bz/oshibana-art-by-tatiana-berdnik/

James D. McCabe, ‘The Language and Sentiment of Flowers’, 2003, Applewood Books